Decentralized atomic cloud storage using Bitcoin

Update: 7/12/17: The biggest flaw with this proposal is that its not atomic with respect to a user’s bandwidth (and this is a crucial concern in a decentralized cloud storage systems.) My conclusion is that payment protocols for these systems cannot be made much more low trust than a standard micro-payment channel (unless there is some use-case where bandwidth can be ignored but I can’t think of one.) #

Update: 13/01/17. A recent paper has emerged describing a “new technique” for doing “Atomic Verification Via Private Key Locked Bitcoin Transactions.” This paper is so similar to the scheme I described here 10 months ago that its hard to tell if this is plagiarism or a genuine mistake. It’s also interesting to note that the author’s scheme won’t work on the Bitcoin network since it depends on OP_AND which is currently disabled and their proposal won’t guarantee a file’s availability under attack. #

There’s been a huge shift in recent years towards using peer-to-peer technology to increase the reliability, robustness, and security of Internet-facing services. Perhaps one of the more obvious use-cases is in cloud-based file hosting. With cloud-based hosting you typically have centralized servers that host the user’s content and are then responsible for maintaining the security and reliability of that data. But companies like Sia [0] and Storj [1] see themselves as the alternative to that model.

These new P2P services want to disrupt cloud storage by creating a P2P network that designates ordinary users as the server. These users - called “farmers” - are responsible for providing hard drive space to renters in exchange for cryptocurrency. There’s a lot more to it than that – there is also a protocol for encrypting files [2] and ensuring availability across the network [3] but the idea is that users host the content - not the “service.”

My question at this point is how can we ensure that the person renting the files and the farmer hosting them can transact without having to trust each other (and without the need for a third-party?) I.e. how can we ensure that farmers are guaranteed payment for hosting and providing content? How can we also ensure that the renter gets back the requested content and doesn’t essentially have to pay for garbage? Is there some kind of Bitcoin smart contract that would meet all these requirements?

As it turns out – I think the answer is now a definite “yes.”

I’m going to be describing two new kinds of contracts in this post – a contract that enforces downloads – and a contract that enforces availability of content - all without the need for a third-party.

The first contract uses zero-knowledge proofs [4] [5] for SHA 256 hashes to prove properties of a transaction flow to secure downloads, and the second contract uses the non-deterministic properties of double-spends on the Bitcoin network to do random audits that enforce content availability.

Both contracts need to use segregated witnesses [6] as a fix for transaction malleability so it won’t be possible to implement on Bitcoin for a few more months [7] [11] – however the general idea can be adapted to Ethereum and other blockchains where malleability isn’t currently an issue.

The download contract #

Renters have to pay to store files on Farmers and there shouldn’t be any way for either party to cheat. As a renter – I should only have to pay to retrieve content that I actually uploaded – and I shouldn’t be able to withdraw my money after a farmer graciously provided me with those services. Further more – the farmer should only get paid for providing such services.

Forming the download contract: #

- The renter and the farmer build an ECDSA key pair and exchange hashes of the public keys.

- They then reveal the public keys for the corresponding hashes.

- The public keys are added together using elliptic curve addition.

- This results in a new ECDSA public key whose private key can only be found by adding together both private keys from the renter and farmer.

- The renter generates an AES private key and encrypts their content with that.

- The renter uploads the resulting ciphertext to the farmer.

- The farmer and the renter encrypt their copy of the ciphertext (producing a new ciphertext) with the additive key from step 3. This can be done with something like ElGamal [8].

- The farmer gives back the SHA 256 hash of the resulting ciphertext.

- The renter checks the hash matches the hash of their own “ECDSA encrypted” content and saves a copy of the hash.

- If the content matches their hash – the renter makes a payment to a special Bitcoin address that requires the Farmer to reveal their private key from step 1 (details given later) to spend the coins.

To download a file the process looks like this [9] [10]: #

- The renter downloads the content back from the farmer.

- The renter checks that the returned content matches the hash.

- The renter and farmer sign a series of special transactions that allow the renter’s funds to be claimed by the farmer by revealing his private key.

- When the farmer broadcasts his transactions it simultaneously reveals the secrets needed for the renter to decrypt her file.

What’s interesting about this is that its atomic: the renter either pays to store a file which can be downloaded back in the future or the process fails and they get their money back. The problem is: how do you build a Bitcoin transaction that forces the farmer to reveal their private key?

There certainly are no OP_CODES that are capable of doing that …

(well – there are some but it requires brute forcing a special ECDSA private key which is computationally expensive for both parties [12].) Instead, we’re going to do something kind of special. We’re going to build a transaction scheme that involves signing a chain of transactions in such a way that the signatures that the farmer uses are … provably insecure.

The farmer must use these insecure signatures if they want to claim their coins – and the act of doing so is enough to allow the renter to derive their private key. But how is this done? Well, its based on doing something that you should normally never do – reuse the same number used for an ECDSA signature – and as long as the renter knows what the farmer signed they have the information needed to reconstruct the private key [13].

There’s only one problem with that – the renter needs to know that a serialized transaction actually contains these weak ECDSA signatures before signing the transaction chain … and without knowing what the signatures actually are when they sign the transaction (because otherwise they could use this to derive the key before they should know it in the protocol.)

Zero-knowledge proofs to the rescue #

In Bitcoin, the transaction isn’t signed directly – only the hash of the inputs and outputs based on the SIGHASH settings. This is the key to this protocol. Here’s what’s going to happen. The farmer is going to construct a special transaction template containing their signatures but they are only going to reveal part of the transaction – specifically – they are going to reveal everything except the second half of their signatures [14].

Now what the renter does with this knowledge is create a zero-knowledge SHA 256 proof for the transaction ID (preimage since its double SHA256 hashed) that asserts that a given SHA 256 resulted from using that partial transaction. The preimage for the hash is only partial – the renter doesn’t know the second half of the signature – they only care that the farmer has reused the same R value for two signatures in the same transaction.

Thus - if the farmer can prove that a given hash satisfies these constraints - the renter and the farmer can proceeded with the protocol to create the download contract without either party cheating the other.

Ah yes … but then what’s to stop the farmer from simply changing their signatures after the renter signs, you ask? Well, did I mention the transaction goes to an output that requires the signature of both farmer and renter to redeem – and that further – this requires that the TXID for the transaction containing the weak signatures not to be mutated?

And that previously – the outputs that the weak signature transaction are redeeming requires that the signatures be valid? This is how you force someone to reveal private keys as part of a smart contract scheme without doing anything crazy like producing a zero-knowledge proof validating an entire ECDSA key-generation process (my original idea.)

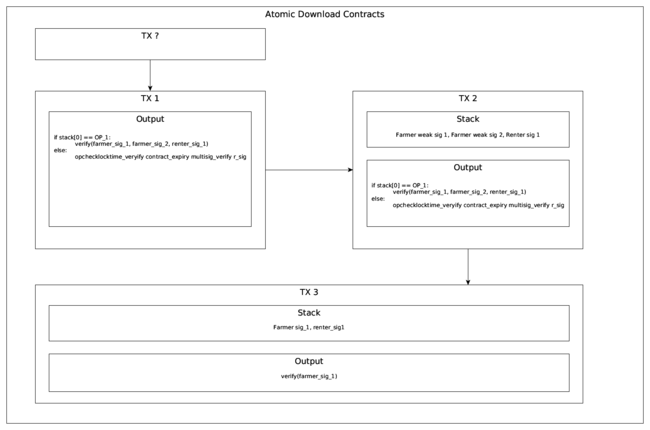

- The renter creates a new transaction TX1 that can be claimed by either: A 3 of 3 multi-sig address OR a time-locked output + the renter’s signature (refund fail-safe.) The multi-signature uses the same public key twice that the farmer previous generated and one of the renters – meaning the farmer must give two signatures to redeem the outputs.

- The farmer generates TX2 that spends the outputs of TX1 to another multi-signature address controlled by the renter and the farmer. This multi-signature address uses totally different ECDSA key pairs to what has been previously generated. (TX2 can also be redeemed after the contract expires by the renter in case the farmer only partially completes the protocol.)

- The farmer signs TX2 using duplicate R values for the signature but does not reveal the transaction content to the renter.

- The renter signs TX2 and gives the signature to the farmer.

- The farmer now has a complete copy of TX2 and could broadcast it if they wanted. However they don’t since they don’t currently have the renter’s signature for TX3 (which would guarantee payment back to them.) Instead, the farmer reveals the SHA 256 hash of the full serialized transaction + the R value used for both signatures. Note: This is not a double SHA 256 hash – just the result of hashing the full serialized transaction once.

- The renter generates a zero-knowledge key pair [15] that validates the serialized transaction format. The proof assets that the weak ECDSA signatures were used in the serialized transaction that resulted in the given SHA 256 hash. The renter gives the proving pair to the farmer.

- The farmer produces a zero-knowledge proof for their SHA 256 hash and gives it to the renter.

- The renter validates the proof – if the proof is valid - the renter SHA 256 hashes the hash to produce a TXID. The TXID is used as the input for TX3 which the renter signs, giving the signature to the farmer.

- The farmer validates the signature. If it’s correct – the farmer now has enough information to generate a valid TX3.

- The farmer broadcasts TX2 which outputs to TX3. When TX2 is confirmed, TX3 will allow the farmer to claim there money. Note: that the process of releasing TX2 gives the renter all the information necessary to decrypt their file.

Generating zero-knowledge proofs #

Generating zero-knowledge proofs is tedious in practice and we’re not going to write any of the code to do this directly. Instead, we’ll just adapt the code that Snarkfront [16] uses for their test_sha.cpp file [17].

Would you believe it – the code already does exactly what we need – it allows us to validate that a preimage matches a given SHA 256 hash as well as assert custom constraints on the preimage – which then become part of the proving and verification key pair.

The way that it does the additional custom constraints is also quite simple: you have a preimage – say the word “test” and you can specify a pattern – lets say eq = t??t. This would work if the preimage really did include a word starting and ending with the letter “t” (plus producing the expected hash of course - the most important part.)

# Zero knowledge proof with satisfied constraints (should pass)

$ echo "hello" | ./test_sha -b 1 -p BN128 -d f572d396fae9206628714fb2ce00f72e94f2258f -e ??ll -n a?a

# Note – the code may need to be modified to accept binary data as hex

# strings but that would be trivial for any C++ programmers.

This software can then be used to create a preimage template for the serialized hash. We don’t actually care what the second half of the signature is so that just becomes ????? … in the equal string. What we care about is that the R values in the signatures are duplicates and that this preimage matches the expected SHA 256 hash.

There’s no need to even worry about validating the sigs directly because if the farmer uses invalid signatures then the transaction won’t confirm and the renter is only signing the next transaction that has that invalid signature TX2 as the input – so Bitcoin does the ECDSA sig validation for us [18].

And … with that we just created a provably insecure signature scheme and then used it directly in a chain of transactions that indirectly pay someone to reveal their ECDSA private keys by reusing R values in signatures [13]. The process now serves to reconstruct the secrets needed to be exchanged to complete a homomorphic encryption scheme for the download based on ECC addition which we then adapted to use ElGamel type stuff [8] [19] to turn it into a public key crypto scheme. Next up: auditing contracts.

The audit contract #

The above contract enforces payments for downloads but what is still missing is a way to enforce storage - the farmer should be paid to store content irrespective of whether the renter decides to download anything since its still taking up space on their drive. One way to do this is to pre-generate a series of hash-based challenges [0].

Essentially, the renter would generate a table of random numbers and record what the result of hashing them was with the data to be stored. To pass the audit the farmer would have to provide a valid hash for a given challenge which would then prove that they still have the content. Payment could then be made from the renter or a third-party based on the audit results - but I’m trying to do this in a way where being paid is guaranteed for passing an audit irrespective of any action from anyone [20].

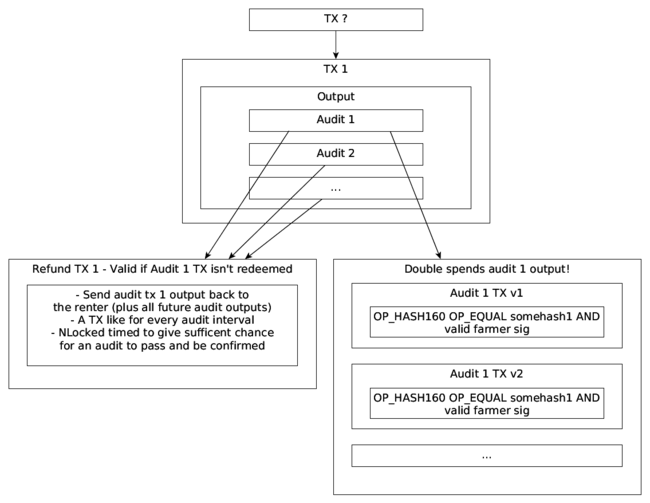

To accomplish this goal - I’m going to create a TX that requires a partial piece of the file to be revealed to claim a coin (using OP_HASH160 and OP_EQUAL [21] [22].) These TXs will occur every N minutes using ntime-locks so that multiple previous audits may be confirmed in a single block.

Every given interval will thus correspond to a new audit and the audits will all be random so the farmer can’t choose a subset of file contents to pass all the audits without storing the full file – it becomes statically unlikely. But how to do this? There’s no OP_RANDOM in Bitcoin … fortunately - the TX confirmation on double spends are notoriously random in Bitcoin.

The audit contract works like this: #

- TX1 funds a number of outputs corresponding to an audit.

- Multiple hash-locked transactions are generated for each output which double spends from the same output.

- Both the farmer and renter can broadcast any of these double spends at any time and the network will race to confirm one of them.

- Another transaction is generated for each audit TX that basically says: I am going to double spend this audit transaction and all future audit outputs after a given time frame. (Its a refund that’s valid after an audit fails.)

In the traditional scheme only the renter is responsible for defining the audit conditions. This means that the renter can theoretically define a series of payments for a given hash that in reality don’t correspond to the hash-based challenge for a file audit at all. In English, the renter could cheat the farmer out of payments for a valid audit as everything relies on trusting the farmer. My scheme solves this problem by making the audits bi-directional.

Both renter and farmer are defining what constitutes a valid audit by progressively defining a series of double-spends for each audit. Neither party knows what will actually be confirmed by the network – its a race condition that becomes statistically unlikely for either party to predict it over time yet the farmer is guaranteed to be paid if they can pass the audit.

The protocol for this is fairly simple. The renter and the farmer keep swapping signatures for the audit double spend TXs until every transaction in the series has been created. The protocol starts out by asking the farmer to sign an audit double-spend TX and give the signature to the renter. At this point the renter has at least one valid transaction for doing the first audit so they know that the farmer at least intends to keep that part of the file.

The renter then exchanges their signature for that TX so the farmer knows that at least they will get paid for keeping that part of the file. The scheme continues like that for the first audit until there are numerous possibilities for the first audit. They then repeat this process for the remaining audits until both sides end up with a list of transactions they can try submit to the network, meaning that neither side knows what will be confirmed.

This means that in essence – the farmer has to keep the whole file around for it to be statistically likely that they will be able to pass all audits as neither side knows what audit will be confirmed. The renter and farmer can now randomly select one double-spend TX to keep for each audit and throw the rest away. The audits could even be given out to a third-party without having to trust anyone someone with any actual money - awesome [23].

Economic attacks #

What’s good about this scheme is that the outcome of contracts are all publicly verifiable on the blockchain - so anyone can see if a farmer failed to pass an audit or if a renter didn’t download any of their files. But there are a few remaining problems – 1. what happens if the renter doesn’t download any of their files (depriving the farmer of the download revenue) or 2. if the farmer passes all audits but still doesn’t give up the download? [24]

I would argue that problem 1 isn’t really a problem at all – if the renter chooses not to download their files back then they’re simply not getting charged for a service they’re not using – after-all the reason why downloads cost money in this context is because bandwidth costs the farmer money so the download contract was created with that in mind [25].

On the other hand – if the renter actually wants to be able to download back their files and the farmer refuses – there should be a consequence for doing that. The way that Sia solves this problem is to use collateral [24] but I think the planned approach that Storj uses is more elegant – proof of stake.

Under PoS you require that the farmer keeps a certain number of coins in a publicly associated address. This proof of stake then becomes their reputation which can be publicly burned if anything goes wrong. So you’re not requiring collateral to be entered into every transaction but the farmer’s long-term reputation and their initial upfront payments are still at stake.

Also consider that the renter can still get back the money they used to front the download contract and I think the game theory dynamics happening for these contracts seems to be the fairest possible for both sides. In a nutshell – this contract dynamics allows for pay-as-you go storage and downloading that simultaneously protects the farmer and the renter while guaranteeing that as long as they uphold their terms of the contract there is a favorable outcome for both sides (i.e. either getting paid or getting their money back + having the service provider punished.)

Tl; dr #

Bitcoin allows for smart contracts to be used to enforce payments for storage and retrieval operations in decentralized cloud storage without the need for a third-party. This is accomplished by using a novel transaction scheme based on zero-knowledge proofs for verifying SHA 256 TXID preimages to prove that a given transaction results in revealing the secrets necessary to decrypt a downloaded file and receive payment for serving it.

The scheme was then extended to enforce long-term file storage by using bi-directionally verifiable random audits based on the properties of double-spends in Bitcoin. Segregated witnesses were also introduced as a solution to TX malleability - as the download contracts are vulnerable to this attack.

Ultra Tl; dr #

You can do decentralized, atomic file hosting using Bitcoin smart contracts without any special OP_CODES or custom blockchains but you need to wait until segregated witnesses are introduced in production.

Footnotes & references #

- [0] http://storj.io/

- [1] http://sia.tech/

- [2] http://storj.io/storj.pdf

- [3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erasure_code

- [4] I believe that zero-knowledge SHA 256 proofs in the context of Bitcoin can be used to accomplish Satoshi’s original purpose of OP_CODESEPERATOR. Details of the discussion can be found here.

- [5] It’s now also possible to do almost all Ethereum-based contracts on top of Bitcoin using ZK-proofs. In the future, this is only going to improve with the introduction of segregated witnesses and practical indistinguishability obfuscation lurking over the horizon.

- [6] https://github.com/CodeShark/bips/blob/segwit/bip-codeshark-jl2012-segwit.mediawiki

- [7] https://bitcoincore.org/en/2015/12/23/capacity-increases-faq/

- [8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ElGamal_encryption

- [9] This is similar to atomic cross chain transfers

- [10] To support multiple downloads of the same ciphertext, the ciphertext that the farmer is storing needs to be decrypted at the end of every download and encrypted with the next key in line.

- [11] The contract can be done now if you’re ok with TX malleability.

- [12] https://lists.linuxfoundation.org/pipermail/lightning-dev/2015-November/000344.html

- [13] http://www.nilsschneider.net/2013/01/28/recovering-bitcoin-private-keys.html

- [14] Cracking this would require brute forcing the remaining random 64 bytes of the signatures.

- [15] The proving / verification pair can be made general-purpose so it only has to be generated once. Then it could be distributed with the software (it’s a few hundred megabytes – less if you compress it.) This would save a lot of computations.

- [16] To install Snarkfront - I recommend installing Debian 8.3. This distribution of Debian comes with version 4.9 of the gcc compiler which is needed to install Snarkfront. I couldn’t get this working on any other version of Debian (and a few versions of Ubuntu) so its quite a pain. I may upload a VirtualBox image in the future if I get time. Special thanks to Anthony Towns and Greg Maxwell for helping me with this.

- [17] https://github.com/jancarlsson/snarkfront/blob/master/test_sha.cpp

- [18] Obviously anyone can mutate TX2 which is why this scheme needs to use segregated witnesses

- [19] https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=196378.0

- [20] Since it’s a “smart contract.”

- [21] https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Script

- [22] A more simple approach is to use micro-payment channels but the game-theory for that isn’t as favourable.

- [23] This process could also be improved a lot to make it more atomic so that valid signatures for the transactions get released to both sides at the same time. I haven’t thought of the solution for this yet. Just a basic scheme so far.

- [24] There’s an excellent discussion on the game theory dynamics for possible solutions to these problems between the Sia and Storj founders: https://forum.sia.tech/topic/21/sia-vs-storj-vs-maidsaef

- [25] I suppose you could argue that if the farmer didn’t agree to this outcome then its a type of DoS attack on the farmer - the renter claims they will pay for a certain number of downloads and then doesn’t use them which ties up hard drive space that could have been leased out to other renters who would execute their downloads. But I think the proof-of-stake section can be a solution to that problem too.